Citybuilders and the culture fantasy play

Mon 14 October 2024"Indeed, the big Other could be defined as the consumer of PR and propaganda, the virtual figure which is required to believe even when no individual can. To use one of Žižek's examples: who was it, for instance, who didn't know that Really Existing Socialism was shabby and corrupt? Not any of the people, who were all too aware of its shortcomings; nor any of the government administrators, who couldn't but know. No, it was the big Other who was deemed not to know."

— Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism

One of the ways we can think about games and play is as "learning culture". That is, through the boundaries of the game the player can model the outside world and re-enact social interactions. For example, children playing house or shopkeepers use the boundaries of the household or shopkeeping fantasy to variously learn what kind of interactions are appropriate in sensible situations within the fantasy: Paying for the apple is appropriate, stealing it from the counter less so. This propensity of play and games to acculturate the player, to make them proper members of society is also why games have a history steeped in empire, colonialism and capitalism. When playing a game the player isn't only abiding by the arbitrary rules of the game, but also by the abstract fantasy of the culture presented. They are playing a culture fantasy.

Anyway, this is just a long-winded way of saying that video games of the citybuilder variety are video games enabling the play of empire.

Let's start with the boundaries of citybuilders, their safety net. In a citybuilder the game is confined to a relatively small map, say 10 kilometres by 10 kilometres in size, on which the player is to mark areas and place buildings for people to live in, for people to work at, for people to consume commodities, and, usually, for people to even consume more abstract things like culture or sports. These types of strategy games are not concerned with dominating other players, real or artificial, across vast distances or even the entire world. They are rather designed to manage the industrial inputs and outputs of the city or region, with the ultimate goal to keep the population happy.

In the most famous game of the genre, SimCity, happiness of the populace is a function of migration: keep your Sims happy and new people will move to your city. See the overall happiness decline and people will pack up their things and leave. Mechanically, this is realised by primarily providing housing and work. Although SimCity obviously uses the aesthetics of late 80s US cityscapes, the people modelled in its fantasy are surprisingly blasé about their consumerist needs. This is mostly attributable to the pseudo-scientific model SimCity is based on wherein people are abstract masses, more akin to coal, iron ore or similar resources. Crucially for SimCity, people are bound to class (low, middle, high income) and are unable to move upward. Instead, when a neighbourhood increases in class the tenants are replaced, assumedly with high income people coming in from the outside and the lower classes moving to other places on the map - or perhaps to another city?

The migration-based-on-happiness-function is, of course, a very neat fantasy of playing an omnipotent mayor. Most people in real life are not able to "just move" if things are taking a downturn. It turns out that people do tend to try to adapt and hold out for as long as they can because social connections and responsibilities as well as property or debt may make moving very costly if at all possible. Of course, there is nothing preventing SimCity - or its more modern incarnation Cities: Skylines - to model this reality in its game mechanics. It could, for instance, present a spreadsheet or a diagram of its population's debt and social mobility and make happiness in some way also dependent on these factors. But the makers of these games rather chose to compartmentalise these contradictions in service of the culture fantasy presented.

This is the fundamental and essential aspect of games alluded to in the first paragraph. Remember the children playing shop? While the children were able to understand the social roles embedded in the shopping experience, what they also learned was how their society at large works: exchange, money, debt, contracts, obligations, all the fundamental components without which a market economy wouldn't be able to function. It is the same with SimCity or Cities: Skylines. While the player can immerse themselves in the mesoeconomics of running a city or region, what the player is also immersing themselves into is how society is supposedly structured: segregated and neoliberal.

This is quite explicitly the case. As Phil Salvador explains: "For [Will] Wright, [lead game designer on many games at Maxis, including the original SimCity], games were a way of helping people create “mental models” for understanding parts of the world. The team at Maxis would research a topic like urban dynamics1 – or something like ant colony behavior, in the case of another game they made called SimAnt – and create a game where players could experiment with those ideas. The goal wasn’t to teach anything directly, but rather to help the player get the model of SimCity in their head, so that playing this game could help them understand how the different systems within a city interact. For many people though, that nuance was lost, and instead they treated it like Maxis could build accurate simulations of the real world." (Emphasis added) Of course, the important bit here is left out. SimCity isn't modeling any city. It is modeling an 80s US city at the height of neoliberal, Friedmanist entrenchment of US politics from a White man's perspective and through a nascent California ideology lens where issues like race or class or patriarchy are wholly ignored or, worse, built-in as natural law.

One of the most levied criticisms of SimCity is its Raeganist monetary system that encourages very low taxes and draconically punishes high taxes. As Paolo Pedercini describes: "In all games of the series if your tax rate is around 12% or higher, citizens get upset. With 20% of taxes, wealthy citizens will simply leave regardless of the services you provide." Similarly, just as the real world Raeganist regime paired deregulation and low taxes with a massive increase in policing, so SimCity too has a pro-police stance that directly links class, education and through both indirectly race with crime generation and how to counteract it. Alexander King writes in Heterotopias: "SimCity encodes pervasive biases about where crime comes from (all people, but especially the poor) and how it is eliminated (exclusively the police). Class becomes the primary pivot to make this assumption work, because how else can it be explained that wealthy areas have fewer police but are safer than poor areas? In reality however, “crime” is socially defined, it is not a fact of nature. “crime” occurs where the police are deployed in order to witness it."

This all results in a simulation that is entirely uninterested in presenting a city as a place where people live and lead their complex lifes. Instead it views its population as an embellishment, an aesthetic that is exactly as important as all other entities like "the industry", "electricity" or "land value". In writing about Cities: Skylines, Dante Douglas identifies this mindset of these games with the mindset of gentrification where the people "are nearly worthless in the eyes of the game, expendable and mattering infinitely less than the social architecture upon which they scuttle." For all intents and purposes, gentrification is the underlying culture fantasy gamefied in SimCity and Cities: Skylines.

Of course, not all citybuilders are adopting the selfsame fantasy SimCity is presenting. One video game of that genre that is quite brazenly eschewing that ideological fantasy is the 2024 released Workers & Resources: Soviet Repulic by 3Division. In it, the fantasy is to be the head of a socialist country during the 1960s to 1980s and create a really existing socialist industrial powerhouse.2 The clear design goal of the game is to conjure the aestheticism of Eastern European socialism as a way to set itself apart from its contemporaries. But by pivoting the citybuilder fantasy away from a capitalist dreamland to a planned economy the game almost by accident reveals how arbitrary and absurd the aesthetics of other games of the genre like SimCity or Cities: Skylines are. If anything, Workers & Resources is the first game of its genre that presents the ideal setting for a citybuilder: The bird's eye view and omnipotent abilities of the player are the quintessence of any planned economy. In fact, in this regard it almost seems ludicrous that the entire genre has such a deep history of presenting almost exclusively free market cities when it is the player - never in-game agents - constantly deciding where residential areas, where "economic areas" and where industrial areas are. Everything in a citybuilder is a player-defined, that is state-controlled, planned economy where the pressures of capitalism are practically non-existent.

But even beyond the aestheticism, Workers & Resources at times subverts the classic SimCity formula mechanically to highlight fascinating things. One of these aspects is that in this game, the people truly are workers and not just abstract entities. If they are not in the player's factories or power plants, for instance because the player did not manage the bus schedule correctly or because the player did not account for work shifts to end, everything halts to a grind. This highlights that in an industrialised country, regardless if it's based on capitalism or Stalinist communism, it is the workers who actually hold the power. It's just like Lisa Simpson sings: They [the player] have the plants, but we [the workers] have the power.

But as we have seen with SimCity, where the overt fantasy of playing a free-market abiding mayor of an up and coming town is only a part of the SimCity fantasy and more sinister processes are at play, so Workers & Resources too has a deeper, more sinister fantasy to present than the surface-level fantasy of a planned economy with 1970s East Bloc technology and industry as well as a worker-centric gameplay loop.

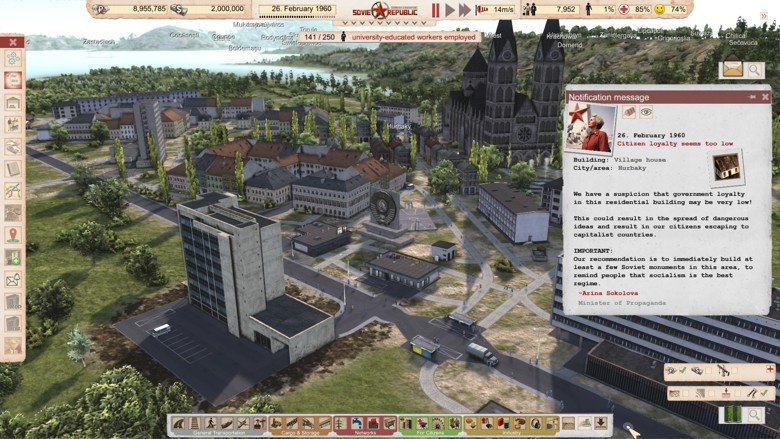

Contrary to its genre siblings, one of the first things advisers are going to demand you put in your city is a secret police building.3 This building is, quite openly and directly, meant to spy on your own population, bug their homes, bully or incarcerate them if they don't follow party lines. Workers & Resources models the migration-based-on-happiness function inherited from SimCity et al. around people "escaping [your republic] to capitalist countries." Notice the phrasing here: Your advisers are explicitly not warning you that your population is migrating away to other cities in the East Bloc or simply "somewhere else", if you don't keep your populace content they'll migrate to SimCity. 4

What's revealed here is quite evidently that Workers & Resources too believes that, to paraphrase Jameson, it's easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism's supremacy. This is strange insofar as the game is as much a sandbox as any other citybuilder but unlike its genre brethren it does not believe it can be played indefinitely. The soviet republic the player builds has a date of expiry and it will succumb to capitalism's reach. The player could design a real existing socialist heaven where no citizen goes without food, clothing, shelter, in-house sanitation, universal health care, universal education, places to meet, to enjoy cultural or sport events, etc. Still the spectre of the Golden West will always spell doom sooner or later. The only method to postpone the inevitable for a few years, Workers & Resources insists, is by state repression.

It's important to note and appreciate that 3Division truly tried to model the infrastructural complexity of really existing socialism as detailed as possible. So detailed, in fact, that at points one has to wonder what the ludic surplus value of some of the systems are.5 In any case, there is an argument to be made that they were simply trying to create an immersive and complete simulation of a socialist, pardon, soviet republic as best as possible and, clearly, state repression by the secret police was a well-documented part of socialist countries. But then again, this line of reasoning falls apart by the game making it exceptionally easy to change the rules of the simulation and basically disable all systems that are not directly related to industrial production and logistics at any time. There are toggles to disable the need for education, the need for research, the need for crime management, fire fighting, even electricity, fresh and waste water. Everything, except the need for spying on one's own population.

This is fascinating as it sheds light onto what is deemed essential to the fantasy of playing socialism and what is not. Workers & Resources argues that it is easier to imagine an East Bloc country without fire hazards, waste management, electricity, water consumption or any form of crime than it is to imagine an East Bloc country without a secret police. While any of the former nuisances - or let's call them externalities - can be toggled on or off to in- or decrease complexity respectively, the repression of its own populace is fundamental to the culture fantasy of "playing" a socialist republic.6

The reduction of socialism to its state repression systems has always been the common refrain of Western societies during and after the Cold War. It is a form of self-serving propaganda that is primarily concerned with legitimising its own violence by pointing the finger at other's violence. Clearly, capitalist societies are not without state repression. One needs not look any further than the existence of the NSA or the GCHQ or the Verfassungsschutz to understand that state repression is likely a function of nation-states not socialism. That these organs are also quite willing to focus their attention on their own populace in capitalist societies is perhaps most viscerally to be seen in the case of the USian MKUltra program. This is of course not to equate police violence or the semi-covert spying of Western countries with the very overt and explicit state terror of socialist countries. The point here, though, is that the centrality of the state repression in Workers & Resources as a core, non-optional mechanic is the core of the violence gamefied in this citybuilders' culture fantasy.

Because this is where all of this ends at: Citybuilders, like their bigger sister the 4X strategy games and their older uncle the wargaming tabletop games, are ostensibly and foremost a fantasy about violence and how the culture at play is based on violence. How that violence is gamefied is where the different genres of strategy games are distinguishing themselves from one another. Citybuilders might, at first glance, look like innocent management games that make their spreadsheet nature simply look more fascinating. But underneath the aesthetics there is a whole map of different kinds of violence reproduced and acculturated, whether it be through gentrification in SimCity or state repression in the case of Workers & Resources.

There is a tendency when talking about these things to brush concerns about violence in video games and society aside by remarking that, well, the world is a violent place so no one should really be surprised that that violence is found everywhere. But that misses the point that these reproductions of violence are not a necessary preclusion to any work of art humans create. They are decisions, if maybe unconscious ones. Just like the children who play shopkeepers because they've seen the socio-cultural situation of going to the shop, we all reproduce our culture through our actions and the things we imagine because we are living in a culture. But unlike the children, given enough time to become mature, responsible people, we are able to reflect upon the culture we are living in and make decisions that might run counter to stereotypical representations. For Workers & Resources, all it would have required is the conscious decision to not include a secret police in the exact same way SimCity or Cities: Skylines decided to do not, or - in absence of that and in service of the amorphous "historical accuracy" - at least a toggle to disable the active repression of the populace in the same way electricity can be turned off. Whether as a state, as a mayor, as an artist, as a game developer, or as an individual, violence is always a choice.

fin

- It must be noted that Urban Dynamics is not a field of scientific inquiry, it is the name of a 1969 heterodox urban planning book by Jay Wright Forrester that made clearly biased assumptions on how cities should be run and designed. ↩︎

- Ironically, although Workers & Resources describes itself as enabling players to build a soviet republic, i.e. a federal but ultimately centrally integrated region in the Soviet Union, in reality it is much more influenced in its design by socialist republics, i.e. the Eastern European countries that were part of the East Bloc, like the GDR, Poland or Czechoslovakia. As an example, the map always makes sure that the player has borders with both other East Bloc states as well as Western countries to enable them to buy and sell resources in both markets. Furthermore, the player always has access to two currencies, the Soviet Ruble and the US Dollar. These are markers for a state that is part of the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance - or more colloquially known as the Warsaw Pact. A Soviet Republic by itself was never in the legal or political position to trade with foreign countries. ↩︎

- It's important to note that this is not the same as a "regular" police building that "fights crime". Workers & Resources has these too and they work in much the same way policing does in SimCity. By contrast, the secret police in this game is modelling the KGB or Stasi. ↩︎

- Moreover, the game renders this impediment absurd by the player always having the option to pay money to "invite" immigrants from other socialist countries and "the third world" with the press of a button and a small fee. Notably, there is no button to "invite" immigrants from Western countries. But now that the game has removed its own constraint (the potential loss of workers) for the player to solve, the game resorts to enforce its repression simulation through repeated and incessant notifications warning about impending emigration to the capitalist enemy. ↩︎

- Why must a player remember to not only connect a water treatment plant, itself fed from a water well, to a water substation but to plop a pump station in-between both the water well and treatment facility and the treatment facility and the water substation, so that the water actually is pumped between the buildings. Wouldn't a water treatment plant not have pumps themselves, eliminating the need for an extra pump building? Why do I need to do that extra work but at the same time do not have to connect each and every building with the water substation. What is the ludic reason for the tiny pump station? ↩︎

- This is technically untrue since the need to provide health care is also non-optional for the player. This, too, is fascinating as the fantasy of socialism presented here goes beyond the psychological control of the citizenry but expands also to their physical bodies, hence also the simulation of the need for food, alcohol and sport. It is biopolitical totalitarianism. ↩︎

flocksy takes

flocksy takes